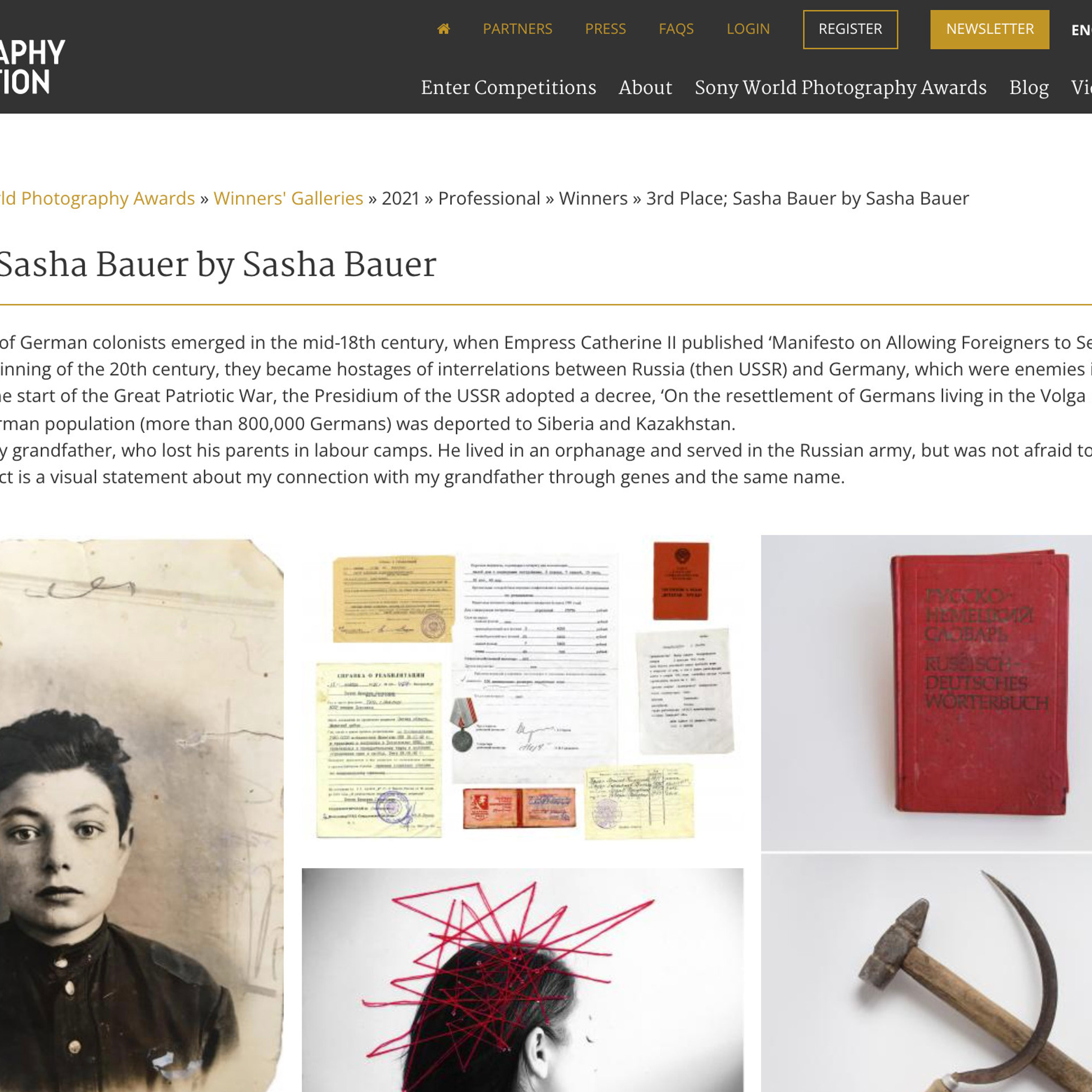

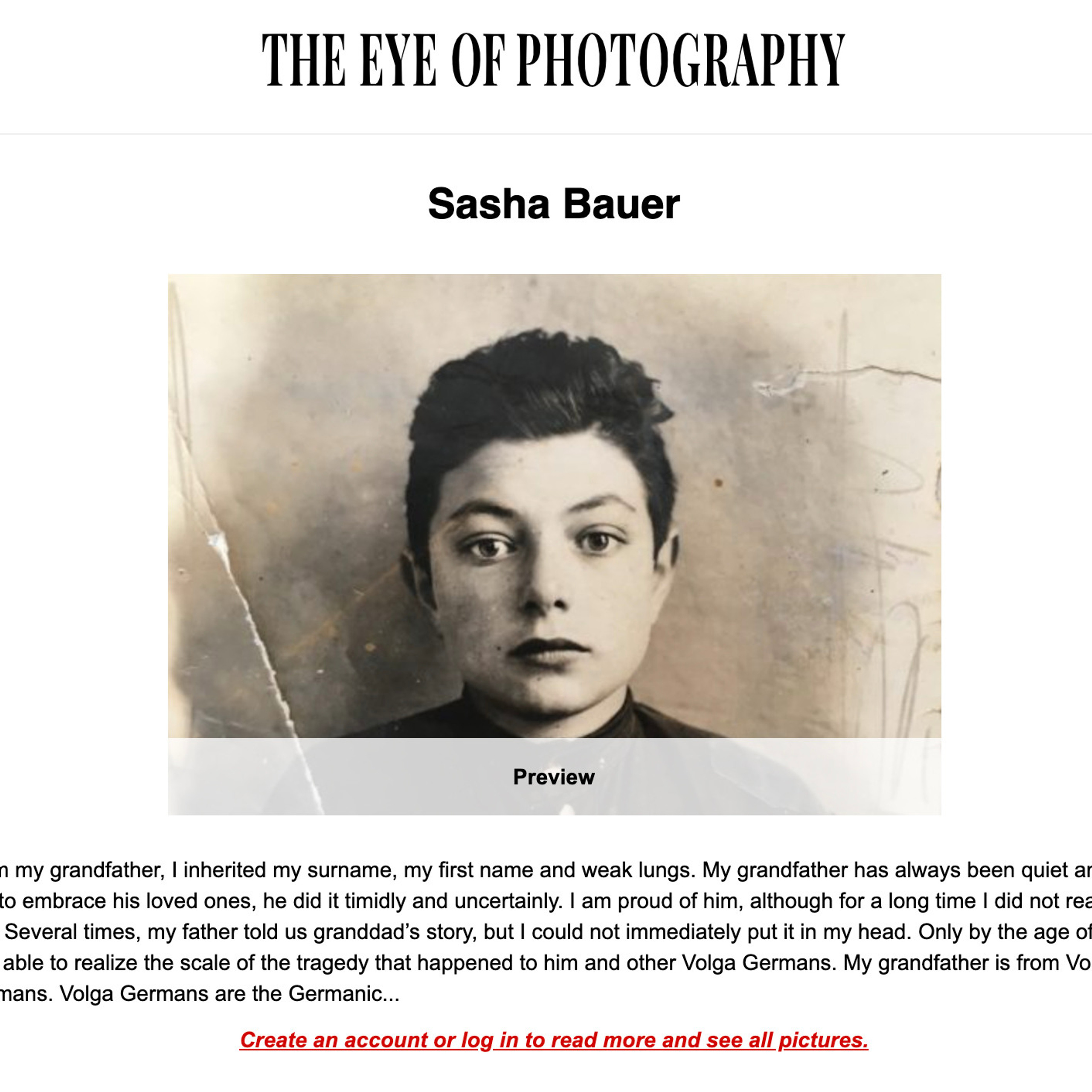

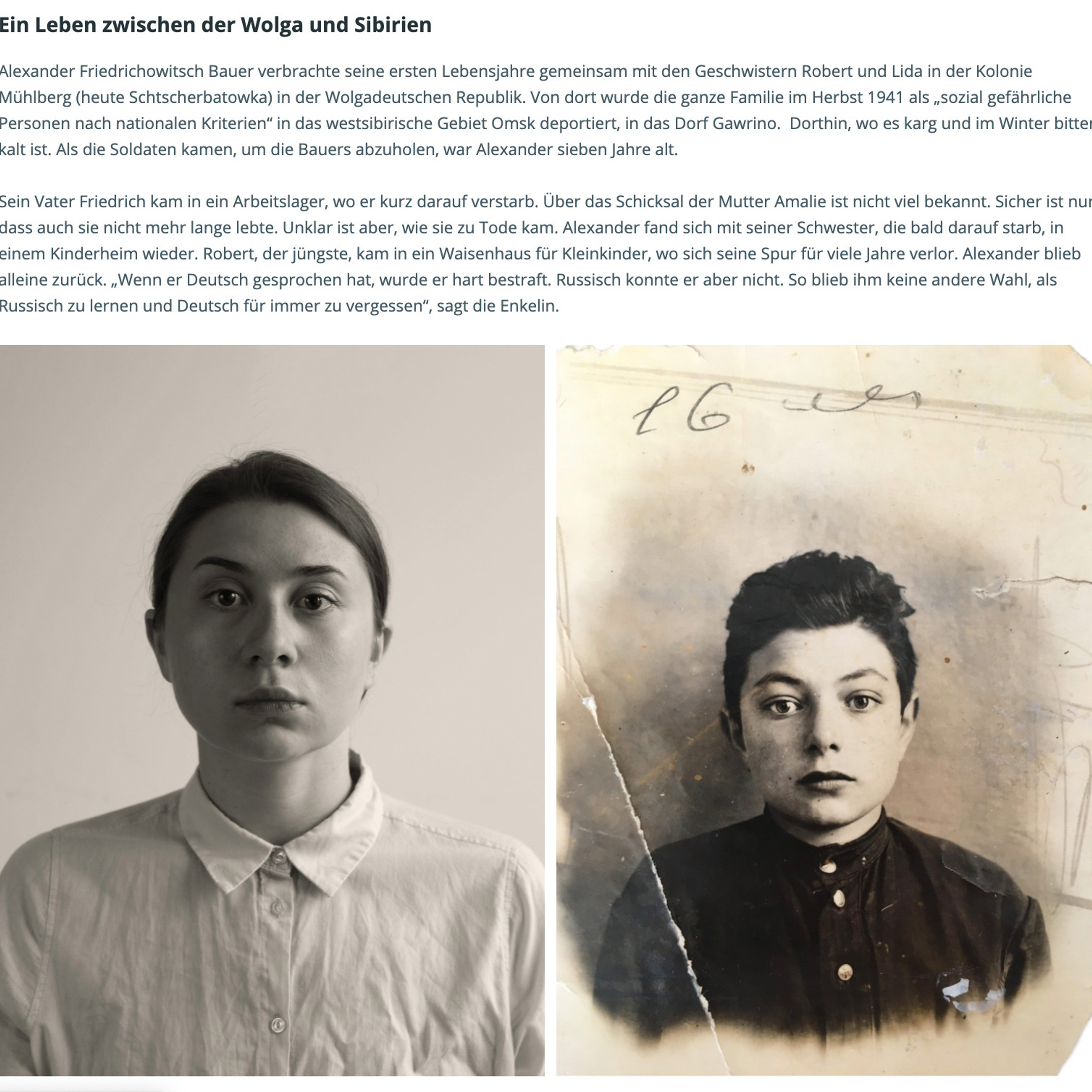

My name is the same as my grandfather’s — Sasha Bauer. From my grandfather, I inherited my surname, my first name and weak lungs. My grandfather has always been quiet and shy to embrace his loved ones, he did it timidly and uncertainly. I am proud of him, although for a long time I did not realize this. Several times, my father told us granddad’s story, but I could not immediately put it in my head. Only by the age of 30, I was able to realize the scale of the tragedy that happened to him and other Volga Germans.

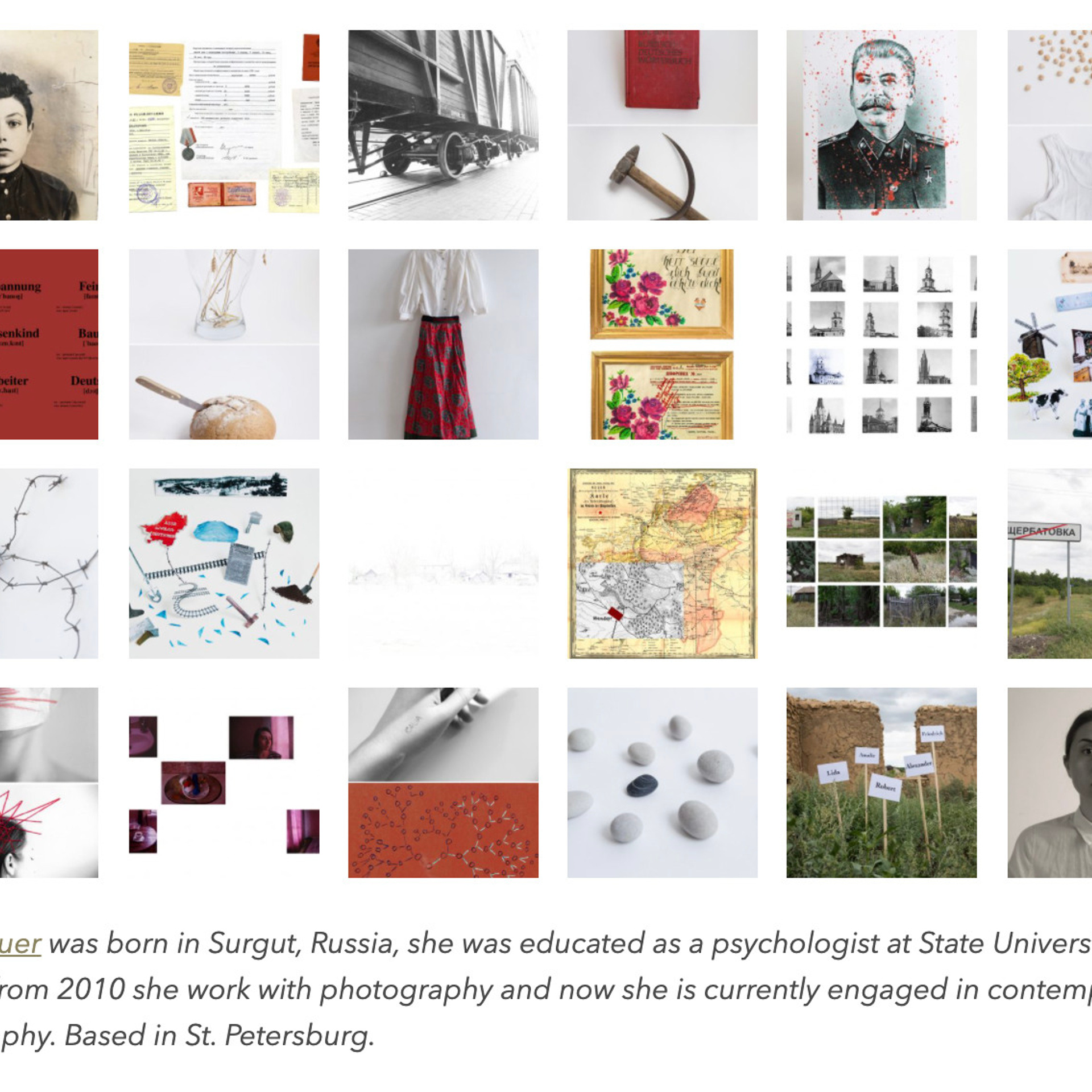

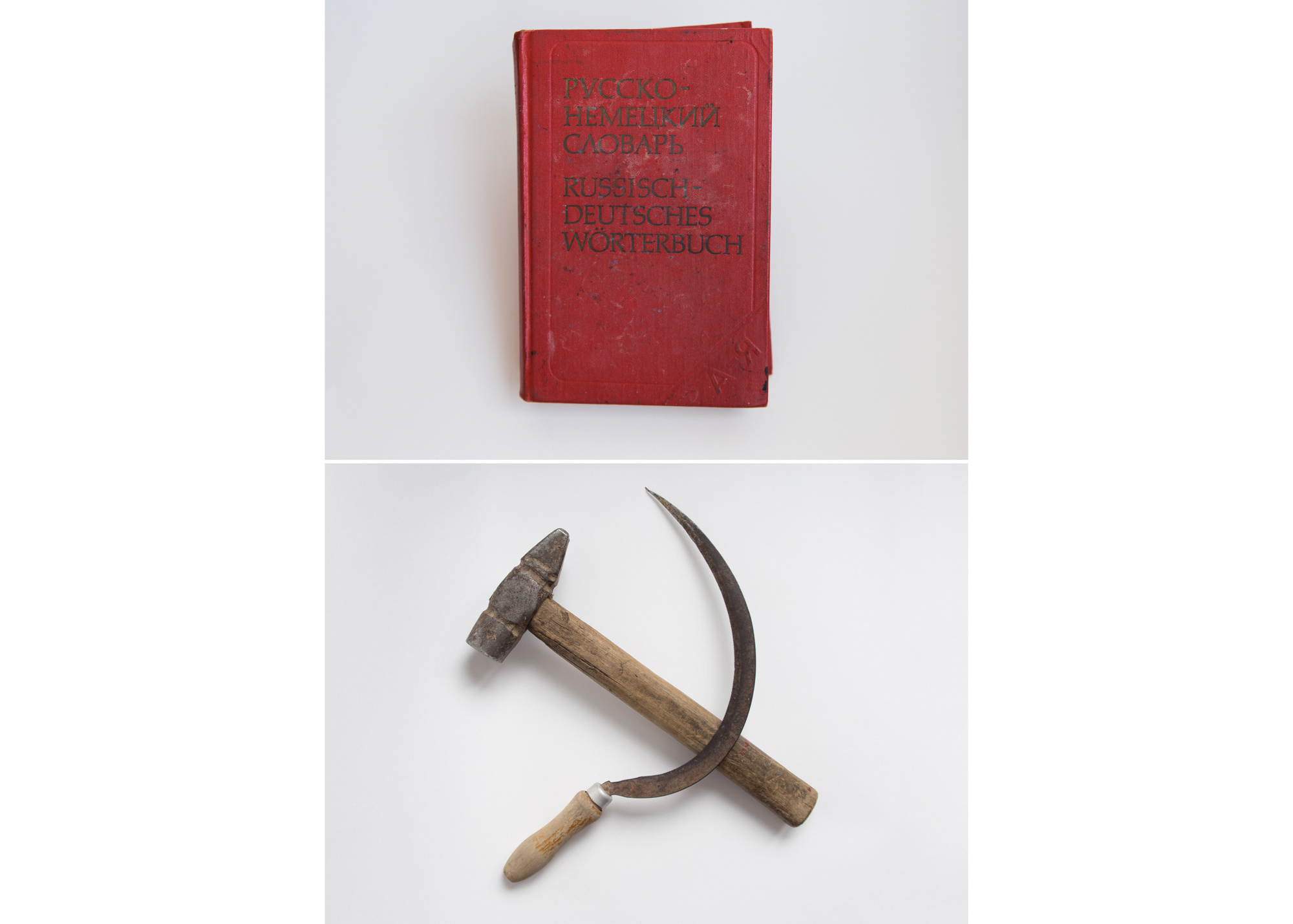

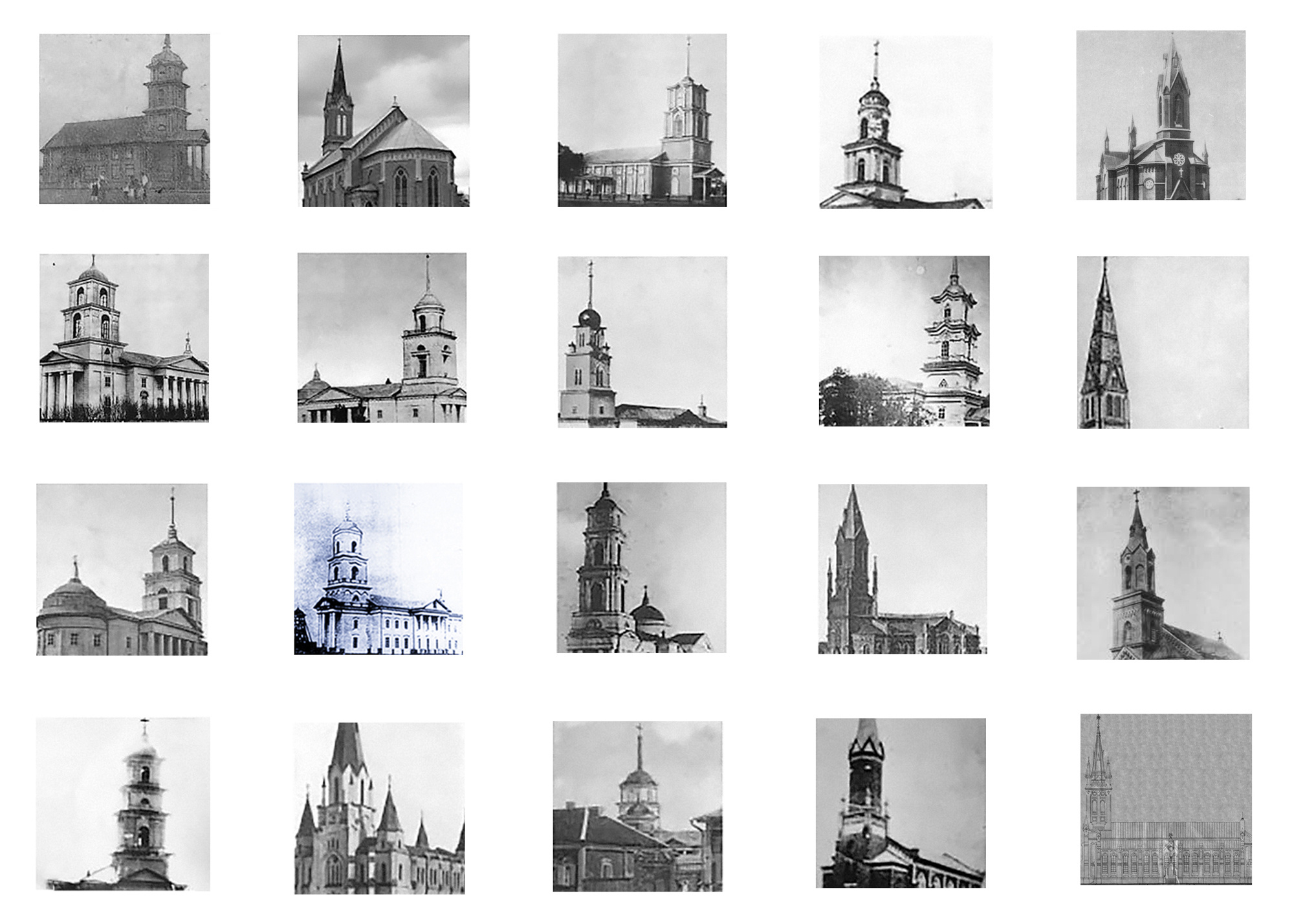

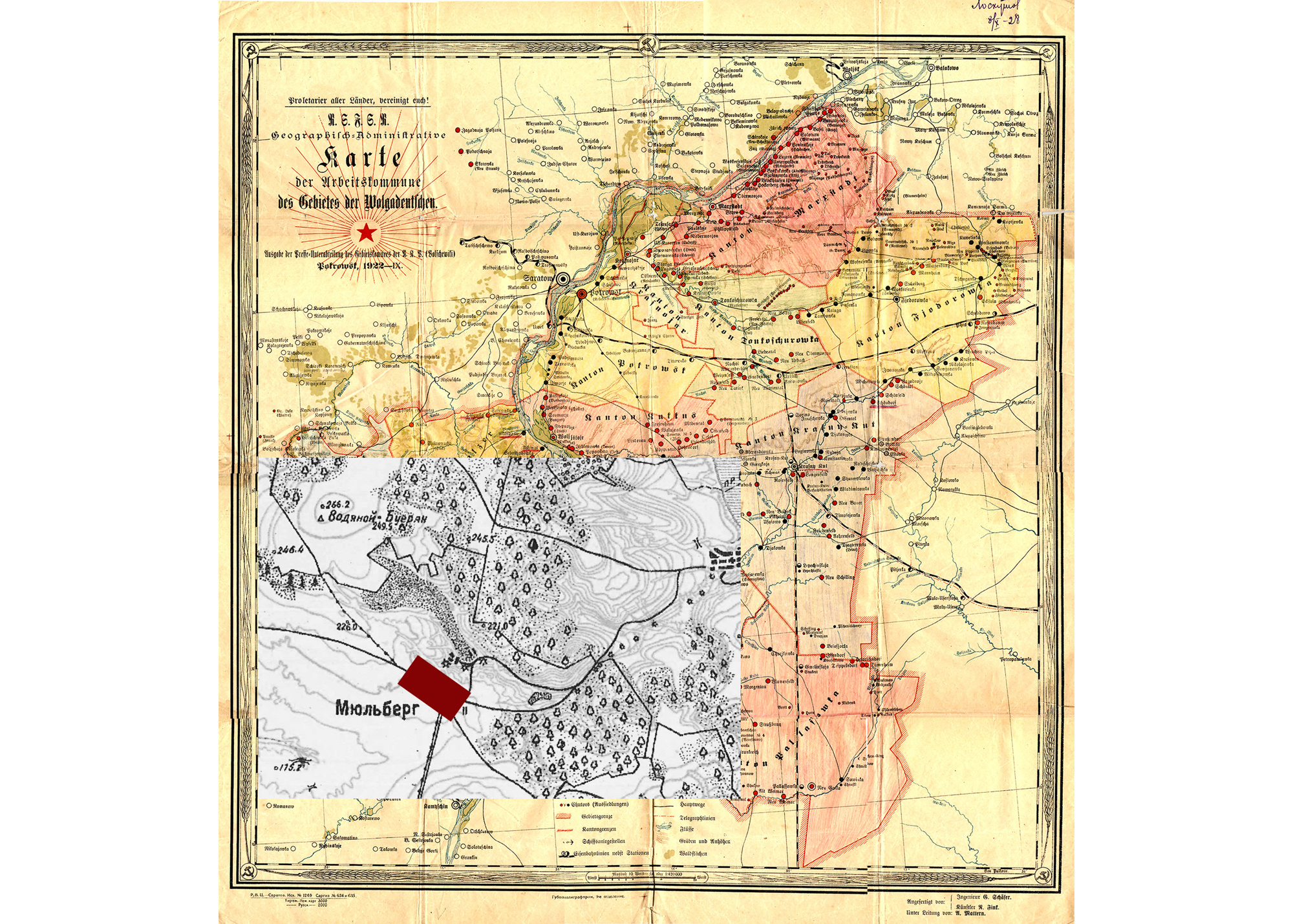

Volga Germans — a Germanic people that settled in Russia in the 1760s at the invitation of Catherine II. Empress believed that their tendency for order and diligence would help to raise the level of agriculture in the country. The Germans lived in closed communities, preserving their customs and language, the villages were given German names. They settled in the Volga region and by the mid-19th century the village Mühlberg (now village Scherbatovka) could be called prosperous and economically developed. This state of affairs lasted until the outbreak of World War II.

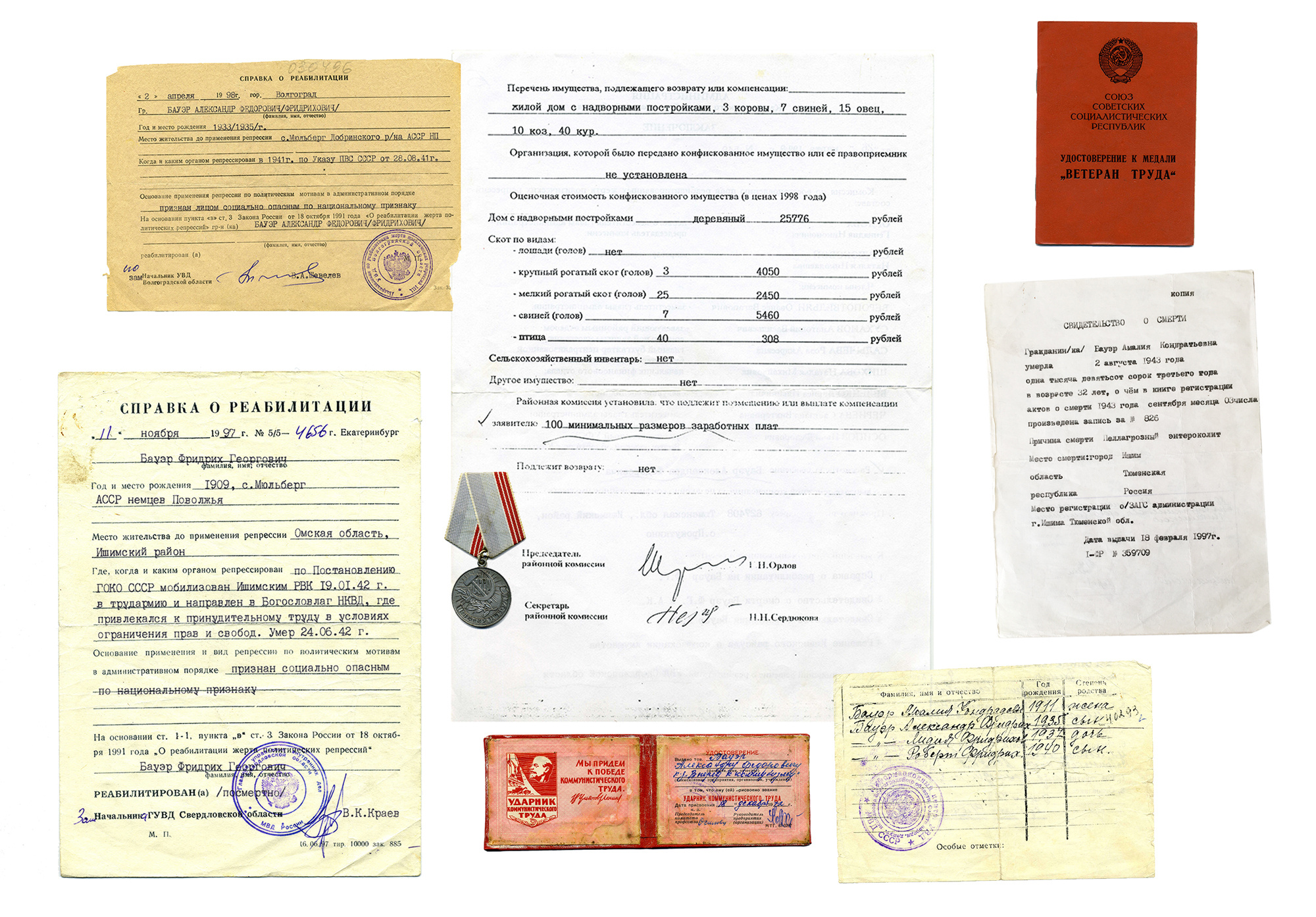

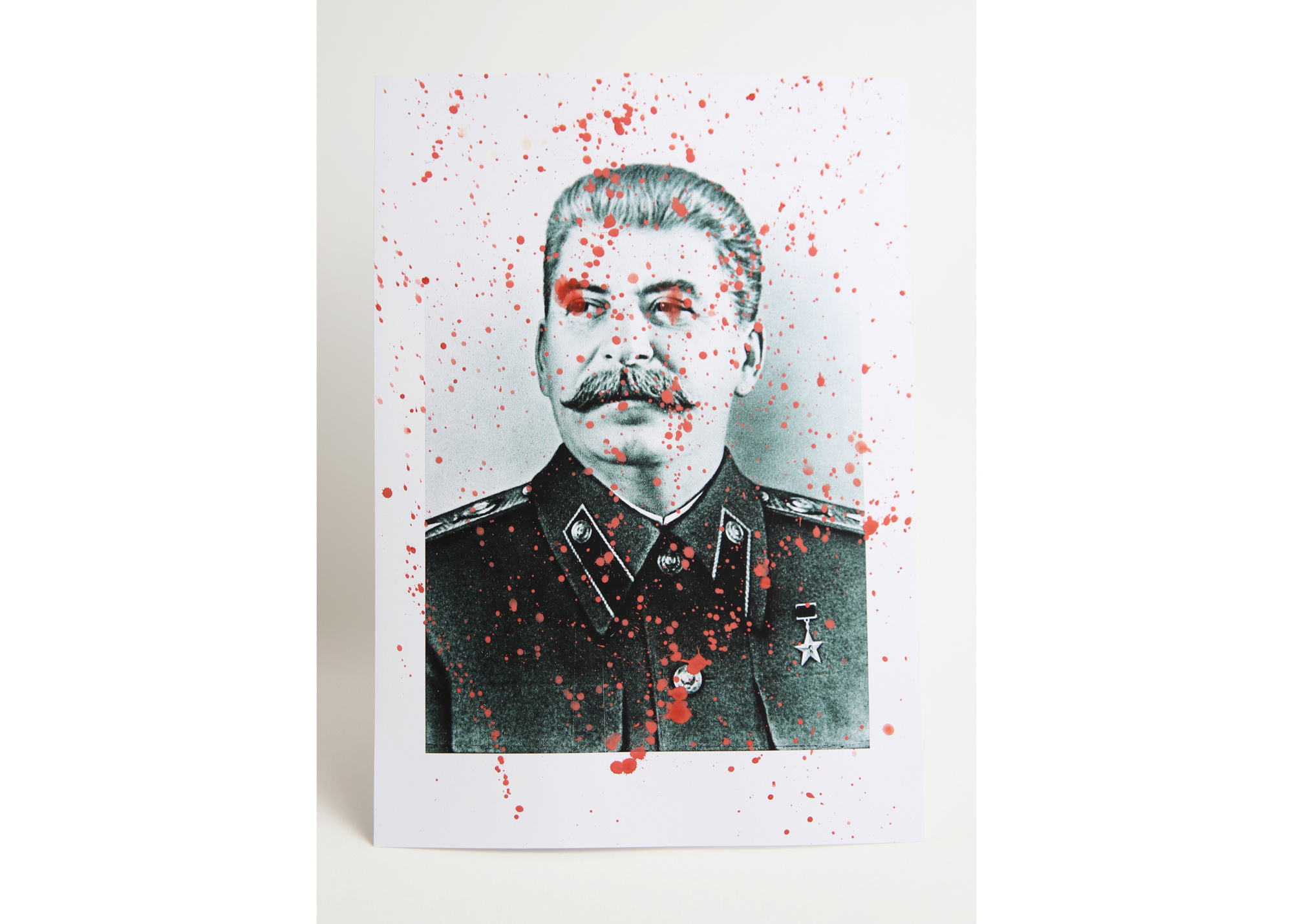

In 1941, Stalin issued a decree that the Volga Germans were recognized as “dangerous by the ethnicity” and were subject to immediate deportation to Siberia. Grandfather, his parents, his younger brother and sister were sent to a village in Omsk region. After that, like many other Volga Germans, parents were sent to labour camps, where they were forced to hard labour without any rights or freedoms. They didn’t return home because both died there. The younger brother was a baby and was sent to a different orphanage for babies. Soon, grandad’s younger sister died in the orphanage. So, at the age of 8, my grandfather was left alone in a big country surrounded by people who were not at all happy with him.

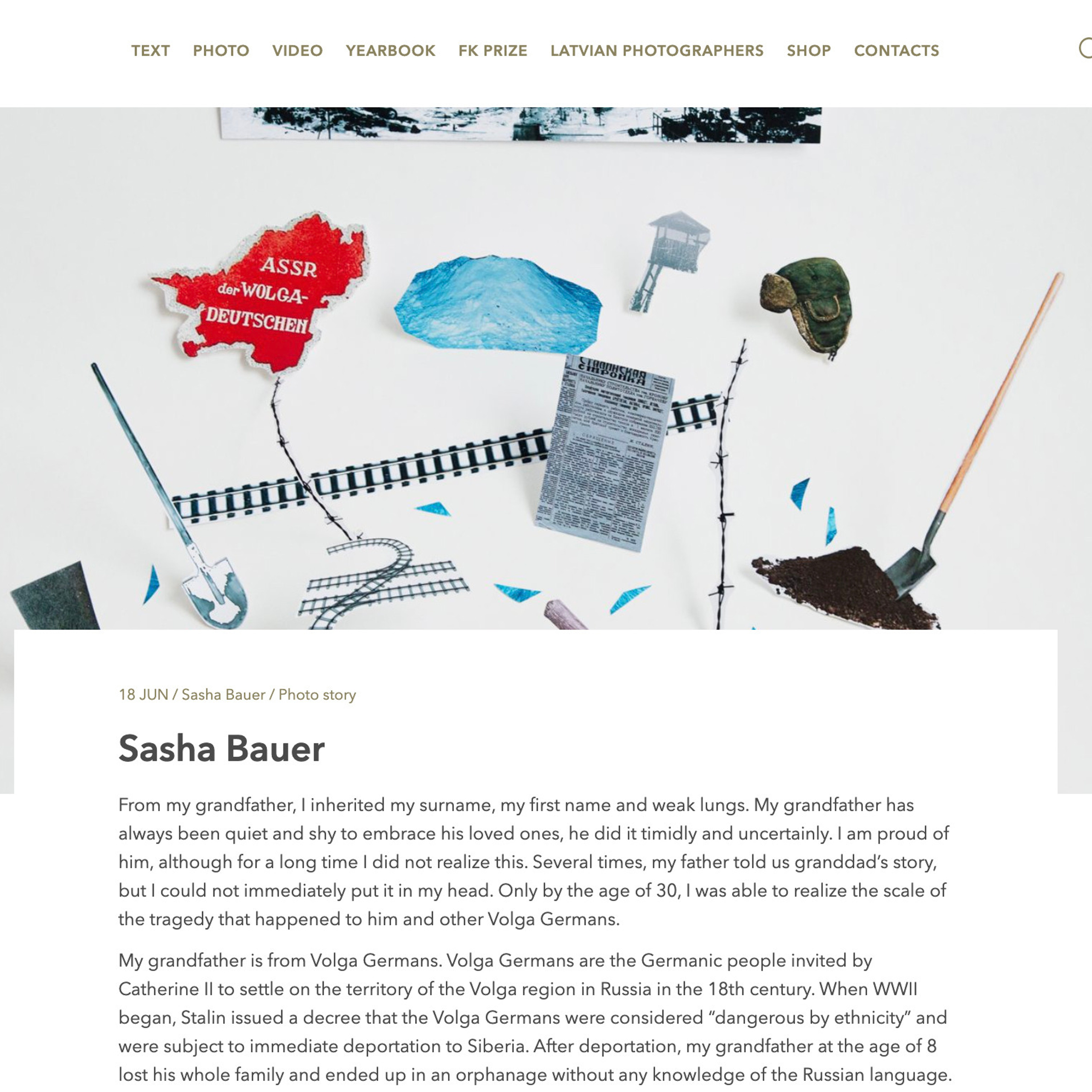

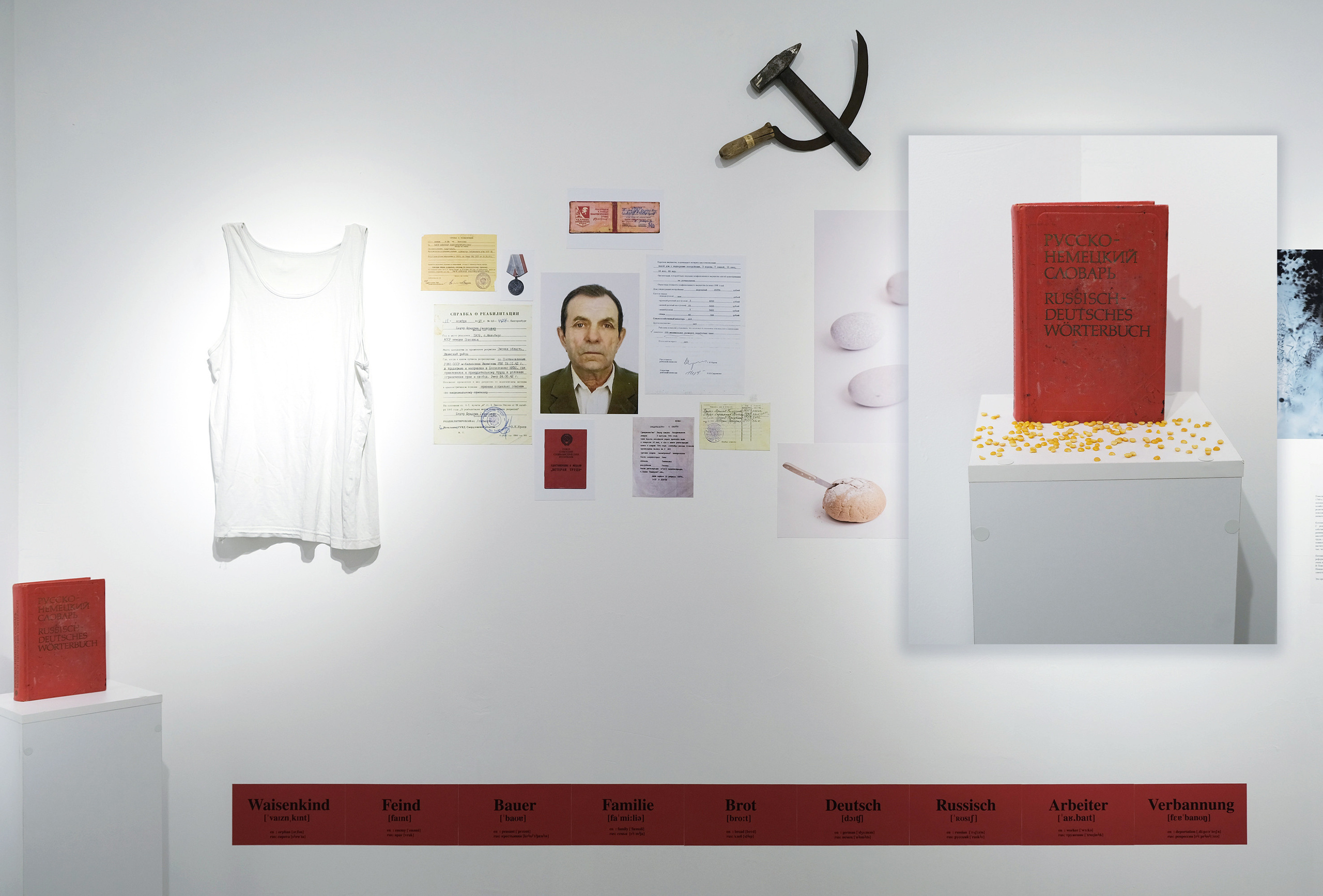

He was cruelly punished for German speech; he did not know the Russian language. Of course, he had no choice but to learn Russian and forget German forever as the source of the greatest pain. At 18, my grandfather went to serve in the Soviet army keeping his last name Bauer contrary to all recommendations. We do not know what it was like for him in the army of post-war Russia with a German surname — he never talked about it. Just like he never talked about his life in the orphanage. His patronymic name in all the documents was however changed from Friedrichovich to Fedorovich.

After the army, he got a job in a state farm and met his future wife, my grandmother. Ukrainian by birth, she was a daughter of a chairman of the collective farm who recently returned from the war with severe wounds. Is it worth explaining that the family was strongly opposed when a feeble young man with a German surname appeared on the threshold of their house and asked them to marry their beloved daughter. But she came out and cut the bread. In Ukrainian customs, this meant that the girl accepts the proposal despite the opinion of her parents. The wedding took place.

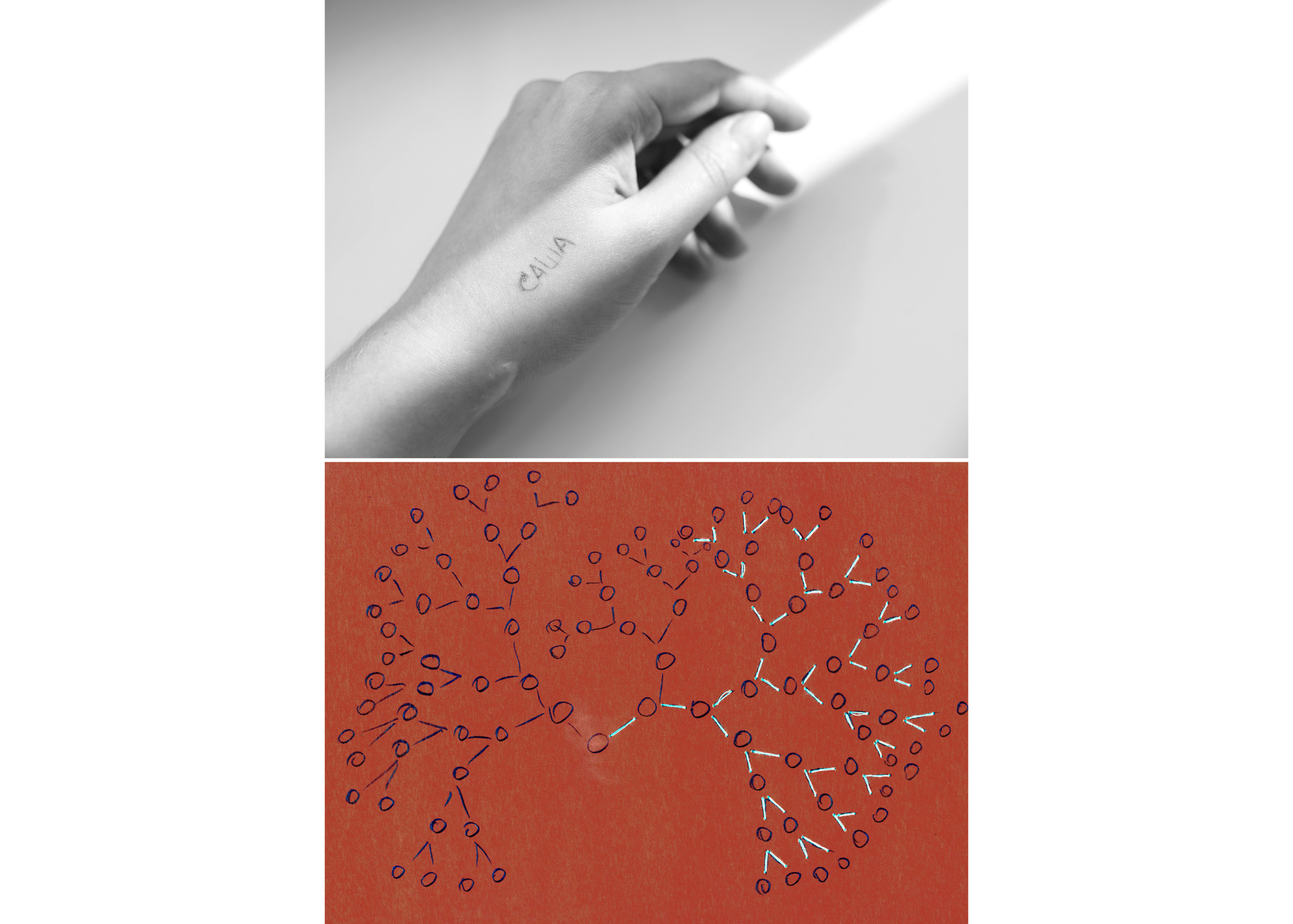

All the subsequent time, my grandfather wrote to various archives in the hope of restoring at least some information and documents because he did not even know where and when his parents died or his date of birth. Also, he was looking for his brother, whom he managed to find many years later.

In this work, I want to explore our relationship with him through genes and name. In many cultures, it is believed that with the name of the ancestor, a person inherits his fate. In psychology, there is a method of B. Hellinger’s constellations. In this method, a person is considered as part of the ancestry system, where he inherits and then can solve the problems of his ancestors.

I was not lucky at school with classmates, I was somewhat different from the rest, and they were hostile to me. Since I was 7 years old, I thought that I needed to solve all the problems myself, I didn’t ask my parents for help, it just didn’t occur to me. Now, I sometimes wonder why I then decided that there was absolutely no one to help me. Why even though I grew up in a good, complete family do I somehow know how orphans feel? In all groups and communities I felt like a black sheep: people treated me either with sympathy, or with caution for no reason. I don’t know for sure how it is all connected but what if I adopted it from my grandfather? And what if, realizing this trauma, reflecting on its history I can change something?

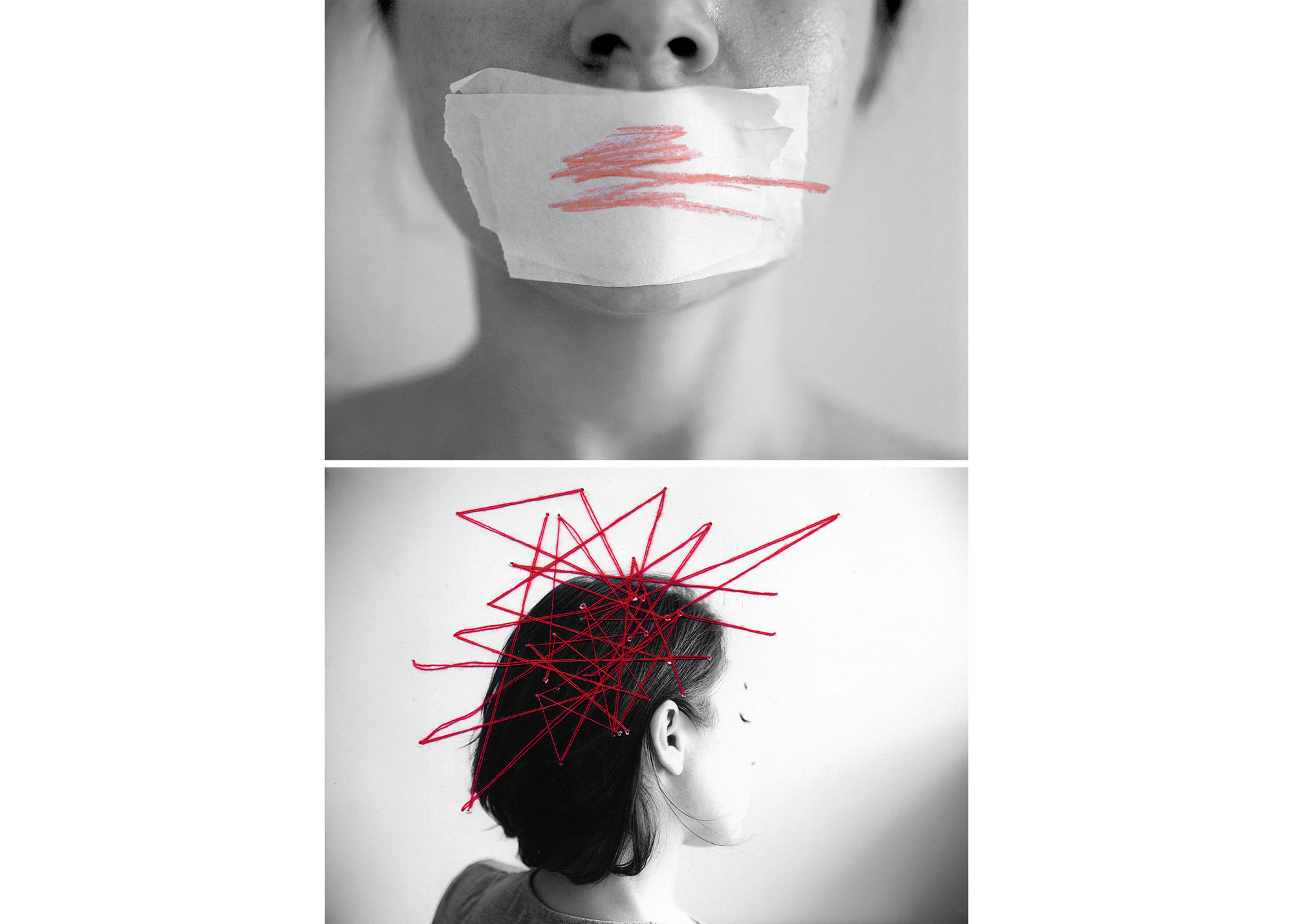

With this work, I also want to draw attention to the fact that due to fear and lack of education for most of the Soviet population then, Volga Germans became a target. They took on the role of scapegoats where people that were traumatized by the recent war let out their anger and resentment on them although Volga Germans had nothing in common with the “fascists” except language.

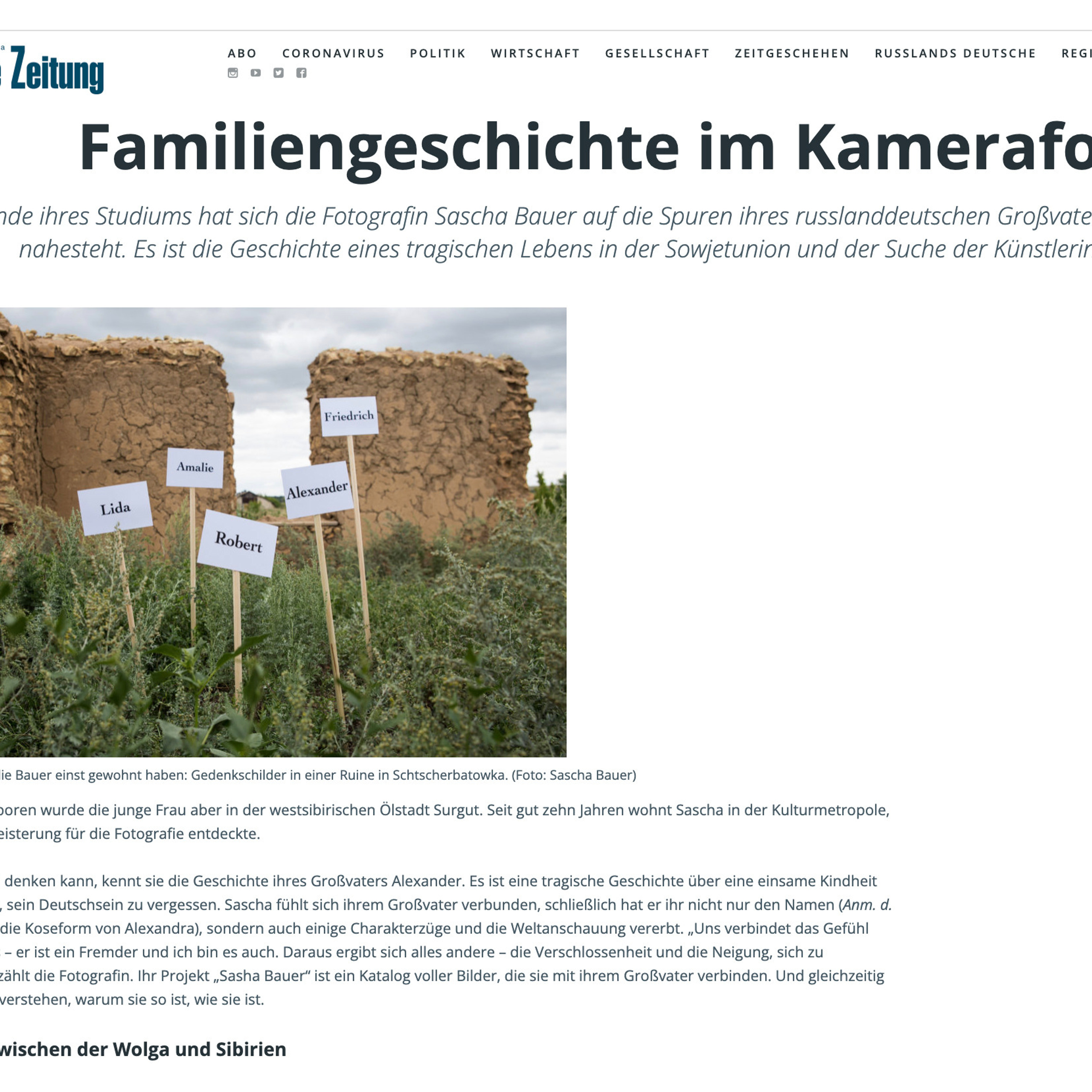

Chapter “Ritual” is an important part of my work where I tell the story of my travel to village Sherbatovka (former Muberg). My grandfather’s family and other Volga Germans were deported from this place in 1941. I didn’t pursue this trip with the journalist’s objectives. It was important to me to see the place of my ancestors with my own eyes, to conduct a “so-called” ritual.

This ritual I expressed physically in the installation: I set up plates with the names of my grandfather’s family members in front of the destroyed house. With this act I symbolically gathered all the family members in the house that was taken away from them — this was an emotionally strong moment for me.

With this statement, I would like to focus the attention on the unpopular historical fact about the Volga Germans gross discrimination at that time. History knows many examples of ruthlessness. I would like to express how severe neglect to human lives leaves painful consequences to many people. Violence leaves its traces in the generations to come.

In our country and culture it is still acceptable to silent many inconvenient historical facts. I see a serious problem with it because we are dealing with distorted traumatised cultural memory which doesn’t allow the entire generations to heal from repressed pain and cruelty. Cruelty is a disease and we cannot heal by silencing it or forgetting. I would like to be one of those who is starting talking.

- In 1942, Volga Germans were repressed with the note “dangerous by ethnicity.”

- My grandfather received official rehabilitation of the victims of repression for himself and his parents only in 1997-1998.

- He received compensation for the property taken away from the family (home, livestock, land) in 1997.

- The amount of compensation amounted to 8349 RUB.

- All grandfather’s adult life he worked diligently for the good of the country, he was given awards “Shock Worker of Communist Labor”, “Veteran of Labor”.

- I have never heard my grandad speak negatively about the government

- My sister and I haven’t changed our surname and hope to pass it on to our children. Grandfather is surprised that now people pay compliments for the German surname, not shame. Secretly, we are proud of the fact that we carry it on.

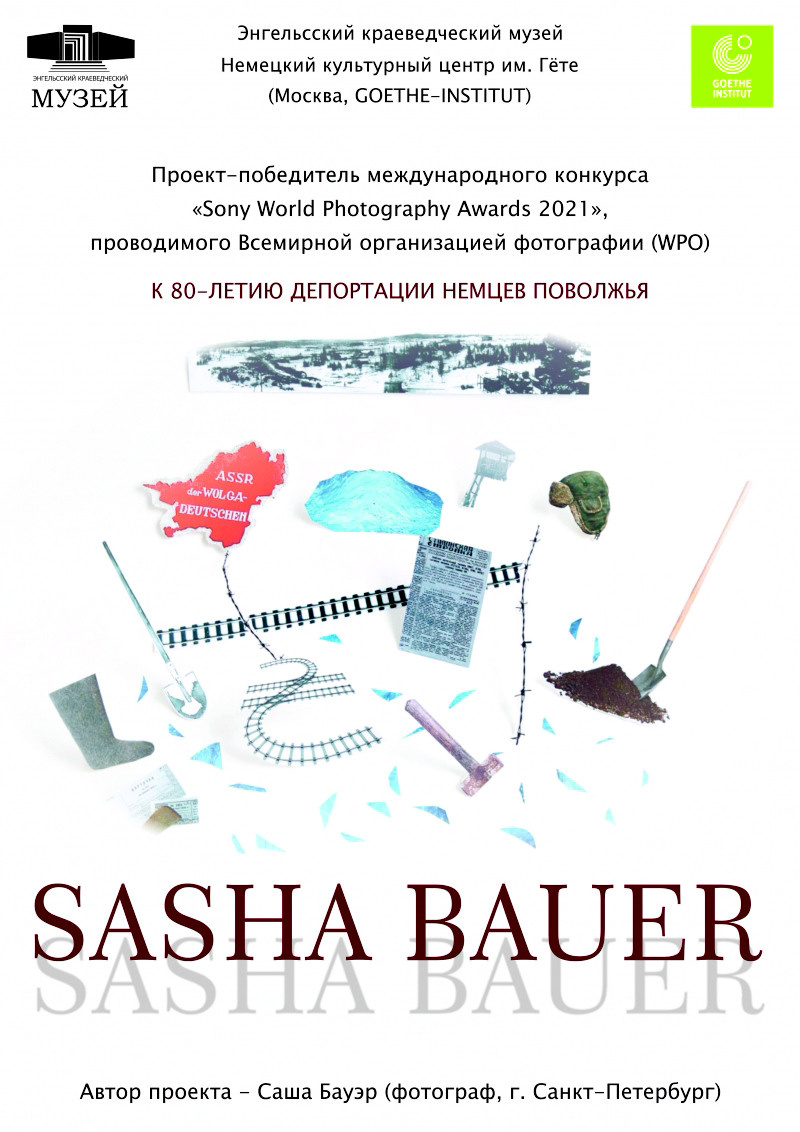

Self-published book “Sasha Bauer”

Sony World Photography Awards 2021 3-d place of Creative category

Publication:

F-stop GROUP EXHIBITION — Issue — Open theme

Notes: For the assistance and costumes provided, my thanks to the German song ensemble “Lorelei” of the Russian-German Meeting Center at the Petrikirkh of St. Petersburg

Publications